|

Search the site:

Bushmills - Irish Whiskey HistoryChapter FiveThe Plantations of UlsterThe Plantation of Ulster was a planned process of colonisation. English and Scottish Protestants were given lands in parts of the counties of Donegal, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Armagh and the entirety of Coleraine. These lands had been taken from the native Irish Catholics after the Gaelic Lord Hugh O’Neill left for Europe. The County of Coleraine no longer exists, but it was created in 1585 by Lord Deputy John Perrott, and it was situated between the rivers Bann and Foyle. Large tracts of O’Cahane’s County as it had previously been known, were put under the charge of Thomas Phillips after capturing Hugh O’Neill’s fort at Toome, on the shores of Lough Neagh. Phillips was described as “a very discreet and valiant commander at all times”, in a book published in 1877. He picked himself out two choice parcels of land and “expanded very considerably soon after he obtained legal posession of the same”. In other words, he made himself at home. Like many of the gentry who landed in Ulster, Captain Thomas Phillips was out to feather his own nest. He acquired a twenty-one year lease on Customs into the area and the ferries on all river crossings into and out of Coleraine. In 1608 he was made a Knight of the realm and the following year he was granted the patent for aqua vitae. At this time there was no whiskey industry. Everyone and anyone could distil. It was a cottage industry, and as much a part of everyday life as butter making or weaving. It was a great way of using up surplus grain. Whiskey didn’t go off, it could be traded or rubbed as a cure-all or taken internally for its ‘medicinal’ properties. During Tudor times it was a common and corrupt practice for the English Crown to sell monopolies. These monopolies or ‘patents’ were sold for just about anything – the importation of sweet wine, the brewing of beer or the distillation of whiskey. In return for either a cash payment or a proportion of the take (hence the term ‘royalty’), the patent holder was given a state-guaranteed monopoly in a particular area, and in turn they could sub-let the licence for whatever rent they could extract. Sir Arthur Chichester succeeded Perrott as Lord Deputy of Ireland, and soon after he granted his deputy, Sir Thomas Phillips, a licence to distil. “To Sir Thomas Phillips, Knt., and such has assignes, as shall be allowed by the chiefe governor of Ireland, was granted on 20th of Apriell, in the sixt yere, licence, for the next seaven yeres, within the countie of Colrane, otherwise called O Cahanes countrey, or within the territorie called the Rowte, in co. Antrim, by himselfe or his servauntes, to make, drawe, and distill such as soe great quantities of aquavite, usquabagh and aqua composita, as he or his assignes shall thinke fitt; and the same to sell, vent, and dispose of to any persons, yeeldinge yerelie the somme 13s 4d etc; with power to sue, arrest and impleade all persons as shall make any aquavite therin, for such paines, penalties and forfeitures, as are limited in the statutes of 3rd and 4th Phillip and Marie, ch. 7, and the same to receave and convert to her or their use, without rendering any account-prohibiting all persons, etc. other than the said Sir Thomas, and his assignes, to make, distill or vent same, upon payne of imprisonment, and such fynes as by the cheife governor and counsell of Ireland shal be thought meete; provided this graunt be not prejudicall to any peers, gentlemen, burgesses, or other persons by said acte excepted; nor to any inhabitant, residinge within the liberties of the countie of Derrie; nor to any licence graunted to any persons, to make aquavite within the places before mentioned; and that this licence do cease and determine, after the expiration of one yere from the date hereof, upon notice given by the chiefe governor, yf it appeare by any cause that same may prove hurtful to the commonwealth.”

It is from this grant of licence to make “aquavite” dated 20th April 1608 that the Old Bushmills distillery claims its ancient heritage. Of course there was no distillery, there were no bottles of whiskey and even the date is now wrong. The British adopted the modern Gregorian calendar in 1752, which means the licence was actually issued on what today is 30th April. By 1609 the Plantation was far from secure, and Sir Thomas Phillips went to London and met the Earl of Salisbury. Irish bandits known as ‘wood-kerne’ were attacking the colonies around Coleraine, and it had become difficult to find settlers. The solution arrived at was ingenious. They would approach the City of London to fund a proper Plantation.

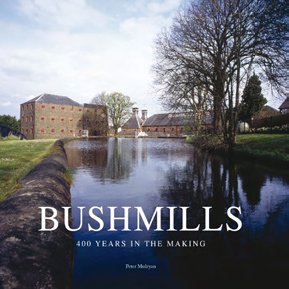

extracted from chapter 5 of 'Bushmills: 400 Years in the Making'

|

[ Back to Top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors